Thangstaken and indigenous resilience

A recent trip to New Mexico led me to discover a timeless community pursuing an inspiring ecorecovery project

Today’s holiday prompts a complicated mix of feelings. Gratitude is always a good thing to feel and express, while a holiday rooted in racist exploitation and ongoing theft is an ironic excuse to embrace it.

My previous posts commemorating today’s holiday have explored the voices of indigenous youth, the back yard garden I cultivated before leaving San Francisco, and my reasons for gratitude in both 2022 and 2023.

A few days after the “Pueblo Spinning, Weaving, & Creativity” event, we visited the Taos Pueblo. It is the oldest continuously inhabited community in the United States, having stood for roughly 1,000 years.

I highly recommend a visit, for several reasons.

I’ve collected those posts below, followed by a few reflections on a recent trip that offered me a new lens on indigenous resilience, environmental stewardship, and intergenerational wisdom.

Indigenous culture & environmental stewardship

Earlier this month, I visited Taos, New Mexico for the first time. A work trip twenty-five years ago gave me an excuse to visit Santa Fe, but this was the first time I had the opportunity to explore more of the state, or to meet and learn from local indigenous elders and youth.

The night after I arrived, a friend brought me to the Taos Center for the Arts for a fascinating event exploring “Pueblo Spinning, Weaving, & Creativity.” It included demonstrations of several traditional weaving techniques developed by tribes from across North America, as well as the process of spinning wool into yarn.

As it happens, we had visited a store earlier in the day that sells yarn, in which the proprietress showed us how a loom works. Between her demonstration and the discovery later that evening of an even more ancient technique, I emerged with a new appreciation for fabric, clothing, and the animals on which humanity long relied to provide them for us.

After the weaving demonstrations, we were grateful to share a native meal of mutton soup seasoned with blue corn jelly, before a documentary screening about an important ecorestoration project undertaken by the Navajo/Diné people. The event concluded with a riveting panel discussion among an intergenerational group of shepherds.

The film that we saw, “A Gift From Talking God (The Navajo Sacred Sheep),” is available on YouTube and runs half an hour. It explores how generations of Navajo shepherds have cultivated the Churro sheep, a subspecies that has played a crucial role in tribal history, as well as the local ecosystem, but was driven to near-extinction—twice—by the federal government.

The film explores the interdependence and mutual reliance of the Navajo/Diné people and the sheep on which they relied for milk, meat, clothing, and sustenance through brutal mountain winters. It also depicts the culture among Navajo/Diné shepherds and their ancient work as environmental stewards.

One theme of the film that struck me related to how indigenous communities treat the animals on whom they depend with such striking reverence. The relationship between the nomadic tribes of the great plains and the bison herds on which they long relied was one I had learned a few things about before. But until last week, I never knew how sheep performed a similar role for sister communities in the west who lived less nomadic, and more pastoral, lives.

Part of the ensuing discussion that I found engrossing related to gender. Whereas western civilization has traditionally separated all people into two genders—and only more recently embraced alternative identities within, between, and transcending them—the Navajo /Diné people have long identified no fewer than five (and according to the panelists, even six) genders. Some of their people, particularly those that Americans might describe as LGBTQ individuals, have been especially respected, and recruited for work as shepherds precisely because they are less inclined towards procreation.

Perhaps the most poignant part of the night was a reflection by a panelist on genocide and its impacts. I’d always thought of indigenous cultural traditions and practices destroyed by the imperial westward expansion as “lost.” But the elder on the panel described how he sees them as merely “asleep,” waiting for future generations to rediscover and revive them. Recalling the notion sends chills down my spine even now, as I write.

A millennium-old indigenous community in Taos

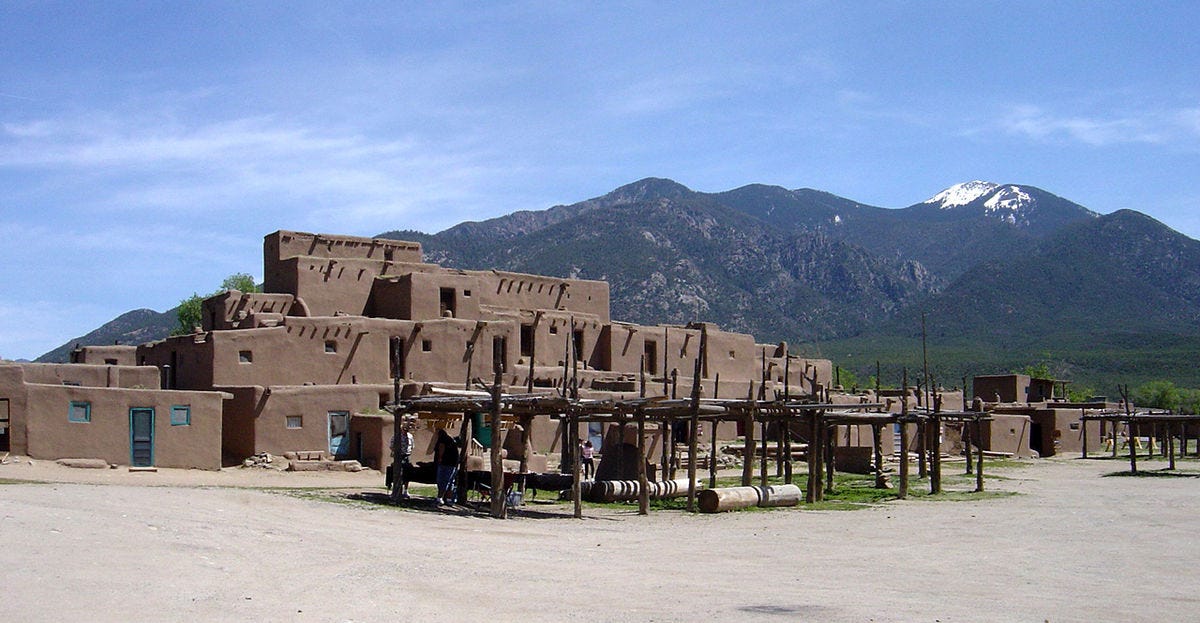

A few days after the “Pueblo Spinning, Weaving, & Creativity” event, my friends & I visited the Taos Pueblo. It is the oldest continuously inhabited community in the United States, having stood for roughly 1,000 years.

I highly recommend a visit, for several reasons.

First, I was surprised to see indigenous American structures that have stood for centuries. My previous exposure to indigenous communities had been largely limited to those with nomadic histories and less permanent architecture, but the two most iconic structures in the Taos pueblos are at least centuries older than the United States.

Second, it was an amazing experience to meet indigenous artisans and learn about their work in the settings where they practiced it. We met people dedicated to making drums, hats, and food, and learned about occasional events open to the public for which I hope to have a chance to visit again.

Finally, the culinary traditions of the Navajo/Diné tickled my palate, and were mostly new to me despite having persisted for far longer than any kind of food I’ve ever thought of as American. From corn jelly to chili jam, and fry bread to mutton soup and sumac pudding, I was thrilled to discover in an ancient culture what seemed to me like such new cuisine.

That visit to New Mexico, like a very different trip to a different desert earlier this year, and the dramatic changes in my life since leaving San Francisco, are among the memories for which I feel gratitude today.

Paid subscribers can gain access to a brief discussion exploring the recent election and its legitimacy, particularly addressing data collected by Elon Musk’s PAC that may have been used to generate fraudulent ballots.

Was the 2024 election stolen?

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Chronicles of a Dying Empire to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.